by Barry Brownstein

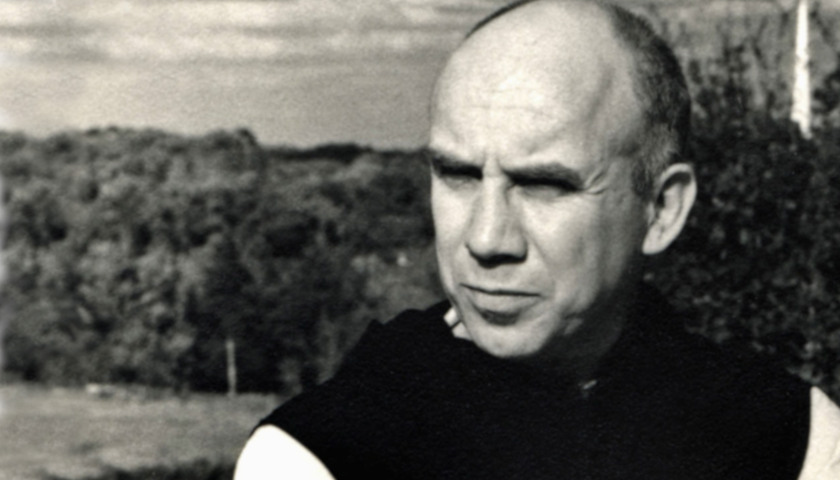

Thomas Merton was a Trappist monk and one of the most important Catholic writers of the 20th century. He was the author of over 60 books; the best known being The Seven Storey Mountain which is an autobiographical account of his search for faith.

Published in 1948, The Seven Storey Mountain is a modern classic, finding a place on The Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s 50 Best Books of the 20th Century list, as well as The 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of the Century list published by National Review.

The Seven Storey Mountain documents Merton’s spiritual conversion, but with a bonus: Merton explains why he turned away from his communist youth. In an age where individuals are increasingly falling for socialist nostrums, Merton provides timeless lessons about why people choose bankrupt ideologies such as communism.

Lesson 1: When people do not understand the conditions under which human beings flourish, there is a smorgasbord of bankrupt ideologies ready to exploit their ignorance.

Why was Merton susceptible to bankrupt ideologies? In The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton points to ignorance:

“I had begun to get the idea that I was a Communist, although I wasn’t quite sure what Communism was. There are a lot of people like that. They do no little harm by virtue of their sheer, stupid inertia, lost in between all camps, in the no-man’s-land of their own confusion. They are fair game for anybody. They can be turned into fascists just as quickly as they can be pulled into line with those who are really Reds.”

Lesson 2: True believers can stay blind to reality for a long time. No one is exempt from psychological biases that screw up our cognitive abilities and decision-making. Today, how many wannabe socialists ignore the daily horrors occurring in Venezuela?

Merton encountered many people in the 1930s in New York City who were communists: “I found the New Masses [an American Marxist magazine] lying around the studios of my friends and, as a matter of fact, a lot of the people I met were either party members or close to being so.” Like others he met, he believed many myths about the Soviet Union:

“I had in my mind the myth that Soviet Russia was the friend of all the arts, and the only place where true art could find a refuge in a world of bourgeois ugliness. Where I ever got that idea is hard to find out, and how I managed to cling to it for so long is harder still, when you consider all the photographs there were, for everyone to see, showing the Red Square with gigantic pictures of Stalin hanging on the walls of the world’s ugliest buildings—not to mention the views of the projected monster monument to Lenin, like a huge mountain of soap-sculpture, and the Little Father of Communism standing on top of it, and sticking out one of his hands.”

Lesson 3: There is all the difference between seeing a problem and recognizing a solution. Merton came to see a fallacy in his own thinking about problems and solutions. The same fallacy is widespread today. For example, there are issues with healthcare and education in America today, but it doesn’t logically follow that a bigger role for government is the solution. Merton learned that it is not enough to see a problem:

“The thing that made Communism seem so plausible to me was my own lack of logic which failed to distinguish between the reality of the evils which Communism was trying to overcome and the validity of its diagnosis and the chosen cure.”

Lesson 4: Just because someone professes to be passionate about solving a problem is not evidence they are more caring than others. Good intentions mean nothing if solutions are destructive policies. Merton wrote:

“I would become one of the hundreds of thousands of people living in America who are willing to buy an occasional Communist pamphlet and listen without rancor to a Communist orator, and to express open dislike of those who attack Communism, just because they are aware that there is a lot of injustice and suffering in the world, and somewhere got the idea that the Communists were the ones who were most sincerely trying to do something about it.”

Lesson 5: There is morality; there are timeless principles of right and wrong. Merton learned the bankruptcy of communists: “They wanted to make everything right, and they denied all the criteria given us for distinguishing between right and wrong.”

Merton learned bitter lessons about those with loud, passionate voices professing solutions with no foundation other than their own “strange, stubborn prejudices”:

“I had formed a kind of an ideal picture of Communism in my mind, and now I found that the reality was a disappointment. I suppose my daydreams were theirs also. But neither dream is true. I had thought that Communists were calm, strong, definite people, with very clear ideas as to what was wrong with everything. Men who knew the solution, and were ready to pay any price to apply the remedy. And their remedy was simple and just and clean, and it would definitely solve all the problems of society, and make men happy, and bring the world peace… But the trouble with their convictions was that they were mostly strange, stubborn prejudices, hammered into their minds by the incantation of statistics, and without any solid intellectual foundation.”

Merton continued, explaining that he came to understand communists had no moral center:

“And having decided that God is an invention of the ruling classes, and having excluded Him, and all moral order with Him, they were trying to establish some kind of a moral system by abolishing all morality in its very source. Indeed, the very word morality was something repugnant to them.”

Lesson 6: Merton’s experience provides a cautionary tale about the dangers of tribalism. Tribalism, in the form of identity politics, is ripping America apart today. Merton experienced tribal hatreds, even among communist factions:

“And so it is an indication of the intellectual instability of Communism, and the weakness of its philosophical foundations, that most Communists are, in actual fact, noisy and shallow and violent people, torn to pieces by petty jealousies and factional hatreds and envies and strife. They shout and show off and generally give the impression that they cordially detest one another even when they are supposed to belong to the same sect. And as for the inter-sectional hatred prevailing between all the different branches of radicalism, it is far bitterer and more virulent than the more or less sweeping and abstract hatred of the big general enemy, capitalism. All this is something of a clue to such things as the wholesale executions of Communists who have moved their chairs to too prominent a position in the ante-chamber of Utopia which the Soviet Union is supposed to be.”

The Seven Storey Mountain is a timeless classic. Those with an open mind and heart can learn from Merton’s mistakes and stop themselves from falling into a socialist mindset.

– – –

Barry Brownstein is professor emeritus of economics and leadership at the University of Baltimore. He is the author of The Inner-Work of Leadership. To receive Barry’s essays subscribe at Mindset Shifts.